Album from the trip

|

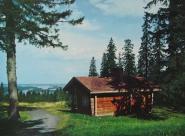

Maija by her lake |

Five years ago I received a letter from my friend Maija about the seven weeks spent alone in her cottage by a remote Finnish lake. Ever since then I longed for a similar experience. I kept discovering more and more reasons why I should go. I became friends with several beautiful Finnish people. I learned that Finland had about 62,000 lakes with 200,000 miles of lakeshore, 30,000 wooded islands, that three quarters of its surface were covered by forest, and that in the northern half, the population density was about five persons per square mile. Because of the Gulf Stream, agriculture and forestry is possible further north than anywhere else, and the history of continuous human habitation stretches 10,000 years back. |

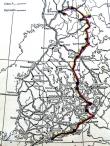

1975 bike trip |

Finland is also the ideal bicyclist's country. There is a good network of roads all the way to the Arctic Sea, beautiful nature, little traffic, cheap public transportation, good food and endless daylight. The time to go is June or July. One should arrive after the thaw, close to the midsummer and before the mosquitoes. The beginning of June seems like the best time for starting a tour - you should in any case make friends before Midsummer's Eve (juhannusaatto - June 21) because that is the night you want to spend drinking and carousing. If you like cities, you should start from Helsinki; the next time I go to Finland I shall start from Rovaniemi (on the Arctic Circle) and head in the direction of Hammerfest (on the Arctic Sea). The most beautiful and the least "modern" areas are in the eastern edge and Lapland. If possible, take a lake boat for part of the way along the Saimaa lake system. A maantiekartta (road map) that you can buy at any gas station for about four dollars, will indicate all the roads you want to know about. Its scale is 1:800,000; much finer maps are available but you won't need them. |

Maija the architect |

The best thing about Finland is its people. In Nixon's idiom, they "have their heads screwed on right." It is pointless and dangerous to generalize, so I won't. From a purely bicyclist's point of view, they are people unusually fond of endurance sports (Paavo Nurmi is a national hero), and they understand the beauty of a long bicycle trip. They are shy, but warm and helpful, and I urge you to meet them halfway by learning some basic Finnish beforehand. Americans are not known for their interest in other people's languages (I am Croatian), but going through the most beautiful parts of Finland means also meeting very few people who speak English. A little Finnish is fun to learn, and I can recommend a good textbook. Another pleasant change is that you'll never have to worry about leaving your bicycle and your gear anywhere. |

|

My bicycle was a French 30-pounder. I am grateful to Ray of Fulton, California's "Mountain Cyclery" for carefully checking it and upgrading it prior to the trip. It withstood the thousand miles of hard pounding, with only three broken spokes and tires (Michelin 700c) worn smooth. I have nothing to add to the conventional wisdom of bicycle touring, except that I prefer a backpack to back panniers. The case has already been eloquently made by S. Ostrander in the February 1974 Bike World (p. 7). I have adopted a small cross-country skiing PAC-I (Cannondale Corp.) by bending its internal frame to fit the contour of my bent back, and loosening its shoulder straps sufficiently to shift most of the weight to the waist belt. All my food and cooking gear was in a handlebar bag (by Hubbard), and the tent, the sleeping bag and the ensolite pad were strapped to a sturdy rear rack. |

|||||||||

|

The whole setup is calculated to squeeze into the international flight weight allowance. My backpack can be carried onto the plane as hand luggage, because it is designed to fit under an airplane seat. The front pannier folds flat and fits into the pack, while the bicycle plus the camping gear weigh right around the allowed 44 pounds. My tent is the excellent but expensive "Wedge" by Jansport (5 lbs. 1 1/z oz.; price is presently about $140.00). If you use this tent, you should add to it four cords and stakes to stabilize it in the wind. |

|||||||||

Clothing should include a woolen cap, gloves and a sweater, a goose down vest or jacket, and a light waterproof jacket - the rest is as usual. |

||||||||||

|

The most useless part of my equipment was a Croatian flag sewn on my backpack. Not one person ever asked me what it was, let alone recognized it. |

|||||||||

The first day I head east along the south Finnish coast. There are several nice old Swedish towns along the route, among them the old capital, Porvoo. It is unusually cold and drizzly for the beginning of June. Toward the evening I pull into Hamina and circle around its center, hoping to meet some people. As inconspicuous as a circus on wheels, I am instantly overtaken by an entire volleyball team on bicycles. After hearing my story, one of them, Petri, invites me to sleep over at his home. First we go to the volleyball courts (built inside a medieval fortification) to see the local firemen demolish some other team, then to Petri's house where his mother stuffs us with Finnish delicacies. Petri is a drummer in the local rock'n'roll band so we spend the evening talking about our travels, Watergate and so on, while listening to Finnish rock and Bob Dylan.

In the morning he goes to the woods (his job is counting trees) and I start my trip inland, enthralled by the peace and the beauty of the forest, and plagued by the stench of truck exhaust lingering over the road. I sit out a spell of rain in Lappeenranta Pizzeria, and continue on a country road. It is bumpy and hilly and when it unexpectedly turns into dirt I am forced to take a long detour, but what bliss to be away from those trucks!

I am speeding over the hills, by the lakes, into the never-ending sunset ahead of me, inhaling the smell of the forest with my every pore. Suddenly the road comes to a stop on the edge of a lake, offering a beautiful view of the little town of Puumala glowing in the sunset on the other side of the lake. After a while, a big noisy ferry pulls up and carries the lone bicyclist to the other shore.

Two girls sitting on the school fence on the main street wave me over and try out their English on me. They take me to the camping grounds and I slide into dreams watching the lake and thinking of their blue eyes. Meanwhile, at the other end, there is something in my new diet that makes me fart fiercely and gives me bad hemorrhoids. On top of this, I cannot feel or use the fingers on my left hand, from leaning too hard on the handlebars.

In the morning I wrap a strip of ensolite over the top of the left handlebar and proceed demoralized over a very hilly road to Savonlinna. I pitch my tent directly across from the imposing medieval fortress which guards the straits to the Saimaa lake, and watch it under the changing light. Tonight there is a fantastic full moon hovering above it. Proximity to the town makes me schizoid - I am in these woods to attain perfect peace, but the full moon makes me fantasize about the beautiful girls I saw while in town.

Disco madness takes over. I put my long trousers on and truck down to the local hotelli where I dance and drink until they throw us all out. It is so light that I cannot go to my tent. I wander around for hours, transfixed by the huge specter of the fading moon and the intensifying colors of dawn.

I rise into a totally uncertain and unpromising morning. My enthusiasm has hit rock bottom and it takes me forever to pack up and get started. During the intermittent rain outbursts I hide in milk drop-offs. They make Finland a bicyclist's haven. They are 4' X 6' wooden cottages on stilts that dot the roadsides all the way into the Arctic. I use them for resting, reading, writing and cooking.

This day it is already 5 pm when the rain finally lets up sufficiently to proceed, but soon the beauty of the forest and the freshness of the road revive me, and I pedal on ecstatically.

A few hours later I stop at a baari in a small village, craving a cup of hot chocolate. The baari is full of young people obviously curious and amused by my appearance. As soon as I sit down I have a drunk 20-year-old girl at my table, wearing my alpine goggles and holding my hands. The tavern relapses into a Breughelian fest; her husband is soon whopping me on the back ("We are all comrades") and simultaneously making threatening gestures at a man at the next table. They insist that I stay with them in their cottage by the lake. I try to disengage myself, to find a Finnish phrase for "I must go" but it is difficult because they have taken my dictionaries and are holding them upside down. Another girl wearing bifocals is approaching. In this fantastic frame, she resembles nothing so much as one of Hieronymus Bosch's fish and tells me in German that her friends are somewhat crazy, and a couple besides, while she is alone.

As soon as I can gulp the chocolate down I am backing out the door, thanking my new friends profusely as they beckon to me from the door, and dashing for the bicycle.

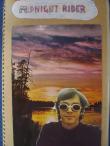

Back in the forest the light rain feels good, and there is still another glorious sunset unfolding before me. It started on my left, and only hours later the sun sinks into the woods straight ahead of me. The birches are ablaze and the mist is drifting over the fields and lakes. As a phantom I glide over the mirror-smooth deserted road into the twilight - I am the Midnight Rider! Sinking into the cool northern night I am finally closing in on Finland. Each succeeding night peels back another layer of the civilization that conceals the mysterious North.

In the daytime civilization reasserts itself. The trucks truck, hotel doormen tell me I cannot enter in bike shorts, people chat with me over fine Finnish beer.

On the bicycle, "civilization" is synonymous with truck exhaust. Off the bicycle, it is infinitely richer. In Kuopio I am mesmerized by the fantastic American "Pilobulos Dance Theatre." They are a highbrow circus; beautiful, funny, as much acrobats as dancers. They coil into surrealistic plasmatic animals, hanging upside down like insects. Outside, there is popular dance in the main square, with a country band sitting in a truck.

Vitri, Outi, and Outi's little sister, whom I met at the theater, take me to the tower above the town, from which I see hundreds of little pine-covered islands dotting the Kuopio lakescape. At seven in the morning we are still sitting in Outi's living room, talking about Finnish politics. The continuous daylight makes us all hyperactive. We go to the farmers' market, buy kalakukko (fish baked in a bread loaf) and take Vitri to work. It has been raining the whole night, and back at the campgrounds my laundry is drenched wet. What's worse, my sleeping bag is wet.

I sleep for a while, and in the evening return to the town, and take a seat in a fancy cafe, armed with my Finnish textbook. In no time four friendly Finns are plying me with beer. They respect my lone biker's courage, but are busy making more sensible plans for me. They'll strap my bicycle on their Volkswagen, and we'll all proceed merrily and speedily northward. Leaving the cafe, we have already lost one companion, who is too smashed to proceed. We are turned away at all doors because my friends are all barely walking. Each one of them is quietly apologizing to me about the two others being so drunk, but alcohol attrition continues and by midnight I've lost them all.

Back at the camp, my clothes hang drenched in the rain, and again I cannot leave Kuopio. I return to Outi with my dripping laundry as pretext and spend such a pleasant, warm day inside that I am tempted to go sprinkle some more water on the laundry. But by the midnight I am back on the road and it is so cold that I am wearing two T-shirts, a sweater, a goose down vest, and even woolen socks over my hands.

After three days of hibernation I am so eager to move that for the first 50 miles my feet don't leave the pedals once. Behind me is an enormous moon, ahead a sunrise; and on my sides a stream of mist-covered fields, cows, haylofts, old farmhouses, songs of awakening birds. Suddenly, at seven in the morning the road changes into a seemingly endless stretch of fist-size sharp boulders, which are shaking my entrails right out of my body. By the time I reach Kaajani I can barely find enough strength to set up the tent. The rain starts up again and inside my wet sleeping bag I am running a fever and falling into more and more vivid sexual dreams. I try a sauna for a cure (they don't fool around here - the sauna is a good 185 deg F), and woolen ski cap and gloves as a precaution, but the fever persists.

Now I am going slowly and cautiously. In Paltaniemi I visit a beautiful old wooden church with an 18th century comic strip depiction of the Last Judgment. It is really lovable.

Further on, in Hyrynsalmi, I stayed at the most beautiful camping site I've ever seen in Finland - a lake lined with white sand beaches and pine forest. I take a rowboat into the middle of the lake and drift there peacefully, sipping beer and (illegally) wooing fish with a piece of salami stuck on a fishing hook. The peace here is absolute; hardly a soul anywhere, and certainly no fish.

The night brings dreams ever more delirious, so the next day I stop at the hospital in Ammiinsaari. It costs less than a dollar to see a doctor. The antibiotics he gives me finally take care of my fever.

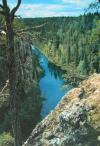

By now I have pretty much left the hustle and bustle of civilization behind. I can ride for an hour without seeing a single house, hearing a single car. This is a northern paradise. No cars, no people, no noise. Every few miles, next to a brook or by a lake is a rest area. The tables and benches are hewn out of entire logs, and even the john is entirely wood, with a nice driftwood door handle.

This evening I am sitting on an old wooden dock jutting into a lake, entranced by the rays of a glorious red sunset tracing out spokes of a cosmic wheel in the heavens above. A flock of geese flies over. I hear birds singing and cuckoo's cuckoo from the woods across, and the sound of fish jumping after bugs. I am in heaven; no more fever, no more piles, no more constipation, no more back pain, no more numb fingers. I crawl into the tent and fall asleep listening to a beautiful song by a bird I cannot identify. The morning is a state of protracted bliss. I float through amniotic fluid to awake bathed by the warm sunlight filtering through the bright azure dome of my tent. I slowly enjoy my breakfast, basking lizard like in the sun; and I am only 80 miles south of the Arctic circle.

Down the road I run into the first reindeer. Their dirty gray coat is so much the color of the glacial boulders strewn across the landscape that I notice them only when they start running away from me. I love the little fawns trotting along with their mothers. The last night had changed me. Now the towns are alien to me, and I enter Kuusamo almost furtively, buy food and leave immediately. Once on the road again the loneliness overtakes me.

I see a young man bicycling in the same direction and strike up a conversation. The young man's name is Vesa, and he works as a printer in Kuusamo. He tells me to follow him. For the next 30 miles we have fun racing each other over hilly and holey dirt roads, deeper and deeper into the country. There are rabbits and reindeer running across our ever-narrower road. Finally we turn onto a tree root footpath ending on a sandy beach. There is a gentle white-haired man washing a car. Vesa talks to him and we get into a small wooden boat, leaving our cycles behind. The little motor is put putting, and in our wake there is an amazing sunset with clouds trailing radially away from the sun. On the opposite end of the horizon the rays are converging to a point, creating an illusion of a sun's faint double.

Our destination is a little island with an old log farmhouse, a scattering of barns and even a savusauna charred black from centuries of use. Reino, the old man and Vesa's father, was born in the farmhouse 61 years ago. He is a Lappish writer and he gives me a stack of his books to look at. They have titles like "Anna minulle atomipommi" ("Give me an Atom Bomb"), and I am burning to find out what they are about, but my Finnish, which is grand for talking about weather and bicycling, fails me now. There is so much I want to learn from Reino and Vesa, but I can learn only as fast as I can look up the words in my dictionaries. Fortunately, among the books there is a picture book about the nature and history of the Kuusamo district (with an English text); through which I learn that Reino is a militant conservationist and deeply concerned with the preservation of the old Finnish and Lappish culture. His island is a miniature preserve of the old northern Finland. The only visible artifacts of our century are a little transistor radio and a typewriter; there is no electricity, no telephone, and no plumbing.

One half of the house is a large room where we all sleep on wooden bunks topped with inch-thick mattresses. This room shares with the kitchen an enormous whitewashed bread stove, on which we cook fresh pike from the lake and polish it off with delicious flat rye bread. I am too excited to sleep - the daylight is continuous, and for hours after my friends have fallen asleep I am still studying Reino's books, the roughly hewn walls, moose antlers, paintings, and furniture. By the time I wake up I find, to my chagrin, that Reino has left the island, and my chance to learn about what he would do with an atom bomb is lost.

The island has a fence across it, and the other half belongs to sheep. A little "under the chin" scrub is all it takes to win the heart of one of them and for the rest of the stroll we are inseparable. When I climb into Vesa's boat, my friend bleats mournfully. We spend the morning rowing around from island to island, checking out little brooks and remains of old houses. When you are thirsty up here you simply stick your head into the lake and drink - the water is perfectly clear.

"Let me make this perfectly clear!" It is the first time in days that a thought of that other world had crossed my mind. Listening to the water gently splashing against our boat, I try to conjure up images of that world - they come out looking something like scenes from the '30s science fiction movies. I start laughing. Sitting at a desk in that other world I've traced out my route on the map, having researched the mean local temperature in June, the average rainfall, the grade of the roads, the length of the day, the train fares, the peculiarities of Ugro-Finnic languages, the "Winter Wars" - so what? How could I have ever planned rowing Vesa's boat? Now I don't care if I ever cross the "Arctic Circle" concocted by some cartographer intent on slicing up my world.

From Vesa's island I am not heading north; I am going straight east, into the wilderness so dear to Reino. Of course, you can only go so far - this "perfectly clear" world of barbed wire and machine guns doesn't allow even reindeer to migrate along the paths that it has been following for thousands of years.

The loss of fear of the dirt roads has opened up a whole new dimension to cycling. On my way to Juuma I surprise two reindeer, give them a chase, and actually overtake them. When they smarten up and run off the road I am in for another surprise - there is still some snow on the ground here.

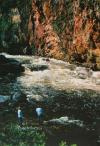

In Juuma I transfer my gear onto my backpack and continue on foot down the Karhunkierros (Bear Trail). It is exciting; it consists of wobbly suspension bridges over rapids, waterfalls still partially in ice, single logs thrown over rapids and long stretches of swooshy swamp. The ground of the northern forest is covered with very thick spongy vegetation, a luxuriant carpet full of treacherous pockets of water. Spider webs, mosquitoes and little black flies are driving me batty. You cannot stop, because you immediately have a cloud of these flies getting into your eyes, mouth and ears so you keep stumbling over the rocks and tree roots, leaping over puddles and creeks, always waving a web-collecting stick in front of you, looking like a delirious blind man.

I race the mosquitoes until four in the morning and collapse above a beautiful lake. My attempts at sleeping last only a few hours, because soon the heat in the tent becomes unbearable. Fortunately, this heat makes all the mosquitoes lumber in the shade, and I have the lake all to myself. For a long time I stand nude on the edge of the lake, with my hands raised toward the sun.

After almost a week spent in the southern rim of Lapland, on June 16 I finally see a little inconspicuous sign by the side of the road: "Arctic Circle." The way I feel, I might be entering the Sahara - the heat and thirst are killing me. Now the sun barely dips below the horizon, and it gets cool only for a few hours - the rest of the time the sun is blazing, and I am being cooked alive inside my tent. Outside, armies of mosquitoes are laying in wait. My trip is becoming more and more frantic - if I ever stop, they'll eat me alive.

My first Arctic town, Kemijarvi, has gypsies sitting on the main street. The Midsummer Arctic is certainly unlike anything I've anticipated. By the fourth day of this freak heat wave, I am well suntanned and nearly delirious from the lack of sleep.

I am on my way to Sodankylli, when a spoke on the cluster side breaks. The last straw - swept by the revulsion toward the Arctic and its perverse heat, I turn around and head back to the cool South.

Immediately, I feel better. There is a nice little lake by the road. I stop, shed my clothes (to the merriment of passing motorists) and dive in. Floating on my back and watching the blue skies above, I feel blissful and full of love toward the Arctic.

I am crossing the Arctic Circle again, but this time in "civilization," so there is a big fake log trinket store and a busload of Japanese tourists "looking" at the Arctic Circle (nothing to see). What amuses me is that as soon as I cross the Circle, there is a cool breeze. Soon after I am in Rovaniemi, back in the unpleasant traffic, exhaust and dust.

Germans razed Rovaniemi to the ground in the last war, so it is an entirely modern town. Among its glistening geometrical architectural boxes I feel like an insect lost on the surface of a manmade aluminum planet. Even the northern light takes on a metallic hue.

In the evening the whole city, except for the main drag, looks deserted. There are the same 10 cars cruising around the block. A few groups of young girls - tight jeans and Brigitte Bardot pouted lips - are standing on the edges of the pavement expectantly. We are all being slowly eaten by the Arctic mosquitoes as we stoically sit and wait.

A Mustang stops and the pouted lips pile in. I watch them drive by 10 or 20 times. A motorcyclist in tan socks passes by - he's got crutches stuck on the back of his bike. Even on this metallic planet Bosch is with us - a cripple rides his cart down the street; here passes a pudgy old Finn with a face shriveled and bright red from koskinkorva (Finnish vodka) and with an equally misshapen and discolored wife. The pouted lips are back at the traffic sign on the corner. Above us a "disco" with soul music and people leaning out of the windows to watch the street action. Still further up, the never ending Arctic daylight that is driving us all crazy, making us frantic 24 hours a day.

Rovaniemi gives me a feeling of what our colonies in outer space will feel like. It happens to be in the Arctic, but it is not of the Arctic - it is an outpost of our civilization. However, the next day I visit the friends of a friend who live only eight miles away, and reestablish the connection with the old Arctic. While I was in Rovaniemi, I never exchanged one word with anyone, but it takes me only one day to fall irrevocably in love with the people who are the lifeline to that past. They are Elsa, an artist and a weaver of Lappish rugs; Matti, a photographer of the Arctic and its peoples; Katariina, a silversmith, and others living and working with them.

The main building on their farm is an amazing centuries-old chimneyless farmhouse that they have found somewhere (virtually everything here has been destroyed by the retreating Germans) and rebuilt here. Its interior is full of beautiful old peasant furniture, embroideries, linen and Elsa's rugs. How I regret I haven't started my tour from this home. I could have spent months here, just quietly poring through all the art, all the books, all the history accumulated; enjoying the food, playing with the dogs, working in the greenhouse, building a fence for the geese, running from the sauna into the river, cutting up wood, contemplating the rugs, the photography and the jewelry. We are speaking to each other in Finnish, German, Swedish, Danish, English, Russian and Croatian (!), and I understand, understand everything. There is so much here I cannot sleep. I go to bed with a pile of books.

Of the books of Matti's photography one is especially beautiful: "Where the Gulf Stream Freezes". It makes me realize that I haven't seen anything yet. The landscape in his pictures is stark and dramatic; Lapps follow their reindeer across the sea, from islands to the winter grazing grounds; fishermen haul in the Arctic fish. To Matti, all the peoples of the Arctic are the members of one circumarctic community. One of the walls of his studio is covered by a huge Mercator map of the Arctic. It is sobering to see our world as a mere periphery of this immense white waste. Matti has traversed northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and Murmansk regions so far; his life project is to circumvent the pole with his camera.

What an amazing life. They live on the Arctic Circle; their summer cottage is the center of Lapland, and their boat is on the Arctic Sea. How I would like to follow them up there! But my train to Helsinki is leaving in the afternoon, and I must get back into my circus gear. Everybody gathers around for a laugh - I get presents, Matti takes my picture, and with a kick in my rear tire, he sends me off.

November 1975; OCR-transfer to MSWord November 2005;

Matti Saanios monumentala bilder väcker känslor

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

|

|

||