On May 11, 2001, Nenad Belic set out from

Cape Cod to row across the Atlantic.

He almost made it.

By Kevin Davis

Nenad

Belic's secret was discovered just before he could slip away undetected

on the journey of his life. He was loading supplies onto a funny-looking

boat that resembled the Beatles' Yellow Submarine, stashing packages of

Rice Krispie treats, trail mix and freeze-dried meals on board, checking

navigational charts and making sure his radio and global-positioning equipment

were in order. Only his family, closest friends and a few confidantes knew

about his seemingly preposterous quest. But a reporter from the Cape Cod

Chronicle heard about this man and his strange boat and went down to the

dock to ask Belic what in the world he was doing. Nenad

Belic's secret was discovered just before he could slip away undetected

on the journey of his life. He was loading supplies onto a funny-looking

boat that resembled the Beatles' Yellow Submarine, stashing packages of

Rice Krispie treats, trail mix and freeze-dried meals on board, checking

navigational charts and making sure his radio and global-positioning equipment

were in order. Only his family, closest friends and a few confidantes knew

about his seemingly preposterous quest. But a reporter from the Cape Cod

Chronicle heard about this man and his strange boat and went down to the

dock to ask Belic what in the world he was doing.

Belic was not pleased with this development. He hesitatingly admitted

that he intended to row solo across the Atlantic. Then he addressed the

question he knew was coming: Why was he doing it?

"It is a question," he said, "to which there is no answer."

His response was either a philosophical statement or a dismissive brushoff.

Whatever the reason for his journey, it couldn't be summarized in a pithy

quote. There was an answer, but it was much more complex, somewhere deep

in his soul.

He wasn't doing it for fame or to break a record. Belic wanted his trip

kept private and asked those who knew about it to refrain from talking

until it was over. He didn't seek corporate sponsors, spending some $50,000

of his own money. He ignored pleas from his wife and daughters not to go

and disregarded advice when he thought he knew better. That was Nenad Belic

stubborn, determined, but lovable.

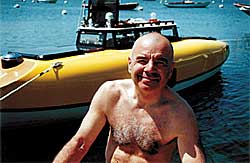

When he left Chatham, Mass., on a sunny May 11, 2001, Belic, 62, a retired

cardiologist from Chicago, was finally free to pursue a dream he had been

putting off most of his life.

A native of Yugoslavia, Belic often talked of his seafaring ancestors.

His father, an engineer, took him sailing on the Adriatric Sea. As a teenager,

Belic wanted to become a merchant marine, to live a life of adventure and

world travel. But he was a practical man, and he knew if he wanted to raise

a family that he would need a more stable life. He chose to become a doctor

and a responsible family man. His adventures would have to wait.

As a researcher,

teacher and practicing physician in Chicago, Belic worked hard, long hours.

"The patients loved him," says Dr. David Koenigsberg, one of his partners

in private practice. "He was very kind and warm." As a researcher,

teacher and practicing physician in Chicago, Belic worked hard, long hours.

"The patients loved him," says Dr. David Koenigsberg, one of his partners

in private practice. "He was very kind and warm."

His best friend was George Matavulj, a fellow Yugoslavian he met 30

years ago in Chicago. They both had a love of the sea and went sailing

in Lake Michigan on a 16-foot catamaran they shared. About 12 years ago,

Belic announced his idea to row across the ocean. "I think you're goddamned

crazy," Matavulj told him.

Matavulj and Belic loved to rattle each other. Matavulj saw Belic not

as some stuffy Gold Coast cardiologist but as a regular, sometimes flawed

man. "He was a mortal human," Matavulj says. "He was curious and full of

wonder. He and I thought life was a joke.

Our feeling was that we're here for a short time, so let's make the

best of it. He never took himself too seriously."

Belic told Matavulj that he wanted to reconnect with the spirit of his

youth, his sense of freedom. Rowing across the ocean seemed like a way

to get there. "It wasn't a macho thing," Matavulj says. "Rowing was about

being an individualist. It would finally allow him, at last, to be in his

own perfect element, to be more of his true self."

He began to talk more excitedly about his plan. It seemed far-fetched,

dangerous and irresponsible for a man who was a husband and father of four.

"I didn't think it was a good idea," says his wife, Ellen Stone-Belic.

"But he felt like he had to do it."

Belic began making inquiries about building an oceangoing rowboat, consulting

books and boating magazines. He asked Matavulj, a more experienced sailor,

for advice. They worked on sketches and contacted naval architects. Most

of the rowboats built for ocean crossings had open canopies, but Belic

wanted an enclosed vessel. He hired Phil Bolger of Gloucester, Mass., to

design the boat and Steve Najjar of Redwood City, Calif., to build it.

Najjar constructed the 21-foot boat with cold molded wood, epoxy and

fiberglass and outfitted it with electronic equipment and solar panels.

The oars stuck out of holes from the sides. Most important, it was self-righting

and presumably unsinkable. "It totally exceeded the design specs in terms

of strength," Najjar says. "I did the best I could to make sure that Nenad

would make it safely from one shore to the other."

Belic named it the LUN, from the Serbo-Croatian word for moon. He told

Najjar it was short for lunatic, because his wife thought he was crazy.

When it was completed in 1993, Belic went to California to give it a

test ride in the Pacific and was thrilled. He and his son Adrian hauled

it to Chicago. He made practice trips on Lake Michigan to Mackinac Island,

carefully tracking the food he ate, the calories he expended, the rhythm

and efficiency of his rowing. He continued to work in private practice

during this time and would wait a few more years before attempting his

big trip.

In 1999, at age 59, Belic decided to retire. He could look back on a good

career during which he served as head of cardiology at Northwestern Memorial

Hospital. "He was always well-respected, and was a very good teacher,"

Koenigsberg says.

In retirement, Belic spent more time savoring life and pursuing artistic

hobbies. He took classes in glass making and ceramics and made lamps. "He

was interested in exploring more creative things," Ellen says. "But I think

this fantasy of rowing kept coming back to him."

His son Roko saw his dad become more philosophical and inquisitive.

"I was unaccustomed to seeing him appreciate things. I think there was

some shift in his perspective," he says. "But obviously, he had it in him,

this desire to explore the ocean. He tried to suppress those desires for

years."

Belic decided he would row from Cape Cod to Portugal in the spring of

2001. According to the London-based Ocean Rowing Society, only six people

have succeeded in crossing solo in a rowboat from west to east, two of

them leaving from Cape Cod, considered one of the more difficult routes

because of the high seas and rough weather of the North Atlantic.

For a man of 62, Belic was in excellent shape. He jogged on the lakefront

and often rode his bicycle from Winnetka to his office in the city. He

had the lean, muscular body of a man half his age. During a trip to the

former Yugoslavia, at the age of 50, he rowed around the island of Rab

on the Adriatic, a family tradition, which takes about 12 hours. But rowing

2,700 miles across the Atlantic was something else. It would be as much

a mental challenge as a physical one. "He knew it was a difficult endeavor,"

son Adrian says. "But he broke it down into tasks. He calculated the amount

of work it would take, the miles, all the steps to achieve his goal."

As the launch date neared, Belic spent hours studying maps and charts

and working out on his rowing machine. He would need help from someone

on shore to provide navigational assistance and weather reports during

his trip. He contacted Jenifer Clark, who, with her husband, Dane, a meteorologist,

runs a company called Jenifer Clark's Gulfstream in Marlboro, Md. They

provide charting and weather information for yacht racers, rowers and others.

Clark liked Belic right away. He was down to earth and humble compared

to some of her other clients. He arranged to visit in March 2001 for a

safety seminar. Clark suggested Belic leave from North Carolina rather

than Cape Cod because he would more quickly catch the Gulf Stream, which

flows northeast along the coast and curves toward Europe and would help

carry him across. She also suggested he bring two Emergency Positioning

Indicating Radio Beacons, (EPIRBs), one to strap to his body in case he

was thrown off the boat. He agreed to take one beacon but insisted he would

leave from Cape Cod. Clark got frustrated. "But he was very sweet and charismatic,"

she says, "and you just had to love him."

Clark also advised him to call Tori Murden, a former client and the

first woman to row solo across the Atlantic, in 2000. Murden was nearly

killed in her first attempt after getting caught in a hurricane. She could

offer Belic advice on handling storms. Belic attempted to contact Murden

a couple of times, but gave up. "I wish he had been more persistent," Clark

says. "That would have made him take this more seriously."

No amount

of talk would change Belic's resolve. Clark looked at Belic and saw in

him what she often sees in people who go on such adventures. "They have

this faraway look in their eyes and they're going to do whatever they want.

It's something they have to do." No amount

of talk would change Belic's resolve. Clark looked at Belic and saw in

him what she often sees in people who go on such adventures. "They have

this faraway look in their eyes and they're going to do whatever they want.

It's something they have to do."

Belic had no intention of failing. Before he left, Ellen took him to

see The Perfect Storm, hoping to frighten him. "He just said that was ridiculous,"

she says. "We had many fights over this. I didn't want him to go. He couldn't

conceive of not making it. He couldn't even conceive of any danger."

It may have seemed selfish for Belic to leave his wife and two teen-age

daughters, Dara and Maia, worrying at home while he risked his life at

sea. To Belic, it was like taking a vacation. He'd be back in a few months.

But the night before he left, Ellen asked him to write a letter to each

family member in case he did not return. He went into his office and wrote

the letters, confident they would never have to be unsealed.

His sons from his first marriage were much more encouraging. They are

both in their 30s. Like their father, they have adventurous spirits. They

are world travelers and award-winning documentary filmmakers. Their movie,

Genghis Blues, about Tuvan throatsinging, was nominated for an Oscar in

2000 and was an audience winner at the Sundance Film Festival. "We definitely

take after my father in that adventurous spirit," Adrian says. "We're guys,

and maybe we have more of that crazy urge to do what others consider silly

and dangerous."

Roko perhaps understood the spiritual side of his dad best. He was working

on a documentary in India about holy men who relinquish the material world

in search of enlightenment. "I'm fascinated by people who would go to such

lengths to find out about their spirituality," he says. "To be in harmony

with nature, or feel at one with the universe, whichever cliché

you can think of, those are worthy goals. We all want to feel connected

to something more than our 9-to-5 jobs. Few people out there do anything

about it. My dad did something about it."

Roko and Adrian went with their father to launch the boat on May 11.

He packed the LUN with freeze-dried meals, crackers, bagel chips, trail

mix, dried fruit, olive oil, water, sardines, a desalinization device,

a satellite phone with Internet access, short-wave radio, global-positioning

units, batteries and a digital music player with jazz and classical music.

After reluctantly talking to the Cape Cod reporter about his trip, Belic

and the torpedo-shaped LUN were towed out of the harbor, and the boys waved

goodbye. Belic was expected to be at sea for two to four months.

The trip got off to a slow start. Belic floundered 60 miles offshore

for a month, unable to get the LUN into the Gulf Stream, wasting valuable

time and food. On June 11 he finally hit the Gulf Stream, 350 miles southeast

of where he started. Had he left from North Carolina, where the Gulf Stream

runs closer to shore, he would have been hundreds of miles farther along.

With his satellite phone, Belic called his wife, sons, friend George

and Jenifer Clark from the sea. He described sea turtles, sharks and dolphin.

"He talked about how beautiful the stars were," Roko says. "He was usually

ecstatic. He was just bubbling."

"His voice always sounded like he was laughing," says Clark, who spoke

with him every Monday and Thursday. "He was joyous. That solitude was something

that energized him." On June 23, the skipper of a 73-foot sailboat on a

pleasure trip with his family encountered Belic's funny-looking craft.

Kenneth M. Campia, a retired real-estate investor from Lake Forest, came

alongside the LUN. "He was having a marvelous time," Campia says. "We talked

a bit and found out we were both from the Chicago area and had mutual acquaintances."

Campia gave Belic some fruit and bread and offered to tow Belic for

a bit, but Belic declined.

"He was very much engaged in what he was doing and wanted to continue

on his own."

By August, Belic was more than three-quarters of the way to Europe,

but running low on food. The risk of getting caught in fall storms was

increasing. On Sept. 18 he radioed a passing freighter, the Rigoletto.

"I told the captain I was rowing across the Atlantic and that it was taking

longer than I expected," Belic said in a phone message to the Ocean Rowing

Society. "I asked if he could spare me some food, he then headed toward

me, came alongside and passed me some wonderful food. You cannot imagine

how great this makes me feel."

A few days later a storm moved in, battering the LUN, but not Belic's

spirits. The last time he spoke with Clark was on Sept. 24. She told him

there was a more serious storm on the way and that he should expect to

be capsized in the high seas. She suggested he call it quits, fasten the

EPIRB to his body and set it off. Belic complained that if he set it off,

someone would rescue him and not the boat. He was scheduled to call again

on Sept. 27 at 10 a.m. When he didn't call, Clark, who had to go out, left

a taped message warning him of worse weather to come with winds up to 50

knots and seas over 20 feet.

Belic spoke to his wife later that day and said he was OK. She pleaded

with him to give up. He told Adrian that he was prepared. "He had brought

in the oars and battened down the hatches," his son says. "He was ready

to ride out the storm."

After Sept. 28, no one heard from Belic. They assumed he was caught

in the storm, which had become furious with winds exceeding 50 knots, gusts

up to 70, and waves with faces as high as 60 feet.

Tori Murden knows what it's like to be alone in a small boat during

rough weather. "The boat never stops moving," she says. "You're always

bruised, you're always battered, you can never stay still. It's mind-boggling

and can be mind-numbing." She was in the same part of the North Atlantic

when she was caught in a hurricane. Her boat was tossed like a toy, capsizing

18 times. She was attached to a tether to make sure she wasn't swept away.

"The waves lose all their form. You can't tell the difference between water

and wind because it's like one big spray. You feel the wave and the water

cross the boat. I thought I would drown."

Murden knew when to call it quits. She set off her EPIRB and was rescued.

Belic finally hit his threshold, though he waited a long time. His beacon

was triggered on Sept 30. The signal was received by the Irish coast guard,

which placed it about 230 miles off the Irish coast. The coast guard sent

out two planes and a helicopter. They found the beacon, but neither Belic

nor the boat was anywhere in sight.

The next day Adrian, who was in New York, learned what happened. He

flew to Ireland to assist in the rescue effort. The Irish and British coast

guard sent out planes, helicopters and boats on a full search for only

the first 24 hours. When Adrian arrived, he persuaded searchers to continue

on a smaller scale for a few more days.

Adrian

chartered planes to search, covering hundreds of miles of rough sea. "Searching

an open sea seemed impossible," he says. Adrian

chartered planes to search, covering hundreds of miles of rough sea. "Searching

an open sea seemed impossible," he says.

As the days continued, the likelihood of finding Belic alive diminished.

Adrian sought help from the local media and asked fishermen and boaters

to keep an eye out for his dad. The sea was cold. If he was in the water,

he already would have succumbed to hypothermia.

On Oct. 9, after it became apparent that changing drift patterns and

sea conditions meant the boat could be anywhere, Adrian halted the search

mission. It was time to go home. His sister Maia's bat mitzvah, which Belic

had planned to attend, was going forward as scheduled. Maia read from her

speech called "The Creation of Light," in which she spoke of how her father's

life was a metaphor for light. She still held onto hope that her dad would

come home.

On Nov. 16 a fishing captain found the LUN floating upside down about

a half-mile off the Irish coast. There was no one on board. It was partially

filled with water, and there was damage to a hatch. Just as it was designed

to do, the LUN stayed afloat. But why wasn't Belic with it" One theory

is that it was capsized by a rogue wave and Belic, perhaps in a panic,

decided to escape through the hatch. "It's hard to get finality when it's

a complete mystery," Adrian says.

Back home, his wife, sons and daughters opened the letters Belic wrote

before leaving. They contained a mix of humor and loving regards. "If you're

reading this, something must have gone drastically wrong," he wrote to

Roko. Though he was never found, the family wanted some kind of closure

and organized a memorial service at the Chicago Sinai Congregation on Dec.

16. Hundreds of Belic's friends, colleagues and family members attended,

taking turns eulogizing the lost adventurer.

"What he could never find in a religious institution, he found on that

trip," Roko said at the service. "I think it was his spiritual journey."

Across the Atlantic at Kilkee, Ireland, a seafaring community where

Adrian spent much of his time during the search, residents lit candles

and made a wreath that they tossed into the sea. It drifted away, as did

the hope of ever learning an answer to the question, Why?

"Those who thought he was crazy just didn't get it," says Belic's friend

George Matavulj. "Those who understand and love the sea know that it can

be irresistibly addictive." Matavulj recalled a conversation he had with

Belic before he left. "We talked about life. We agreed when the time comes,

who wants to die in a hospital with tubes and respirators" He said, "I'd

like to die suddenly, doing something I love." I guess he got his wish." |